Preis der Nationalgalerie für junge Kunst 2009

Award Winner

Omer Fast

(born 1980 in Paris, lives and works in Berlin)

Jury’s statement:

Omer Fast’ s film projects – including the work ‘Nostalgia’ shown in the exhibition – are characterised by performing virtuoso analyses of film as a medium and its various means of expression. Taking the fate of a refugee as a starting-point the artist succeeds in leading the observer from the present time into a fictitious past. This is accomplished with a clever dramaturgy of three film narratives, which produces an impressive psychological density due to the spatial setting and its complexity. Omer Fast is one of the great storytellers of our time.

Shortlist Artists

Keren Cytter

Omer Fast

Annette Kelm

Danh Vo

Shortlist Exhibition

September 11, 2009 – January 3, 2010

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin

Keren Cytter has created three new films for the exhibition. The inspiration for all films are brutal criminal cases which Keren Cytter came across as standard items in the news in the spring of 2009 and which all have bizarre aspects to them. The first case concerns a man who shot his wife in the head after an argument and then turned the gun on himself and died. The woman however survived with the bullet lodged in her head. When a police officer arrived on the scene, he was greeted by the woman and was apparently even served a cup of tea by her. The second, even more grotesque story is about a Russian man who survived leaping from the fifth floor of a block of flats, not once but twice. The man in question, a certain Alexei Roskov, was drunk as he jumped out the window for the first time, apparently motivated by tedium. According to reports, he later explained that he subsequently jumped from the fifth floor for a second time, for the simple reason that he could not bear how his wife got herself worked up nagging at him so loudly about his first jump. In the third incident, a man by the name of Ben Kinsella died in a London suburb after being attacked by three young men. He was stabbed to death – ‘eleven times in the spate of five seconds, according to reports.’

For the three films in the exhibition, Keren Cytter has recreated the key scenes from these appalling cases using members of her recently founded dance ensemble, D.I.E. NOW (Dance International Europe Now), and set them in new contexts. The dialogue in the films has, for instance, been invented by the artist and emphasizes the bitter irony of each. The film scenes were neither created in Russia nor London, but rather in flats and other locations in Berlin and remain unspecified. The film set does however take on a narrative role through the objects shown and used, through the use of music from a cool 60s crime series (here in a modern remix) and in particular through the trashiness of the whole architectural ambience. The reality of the various stories, which is hard to believe as it is, slips into the fictional, into the metaphorical and yet retains its intensity. Recent drawings, which Keren Cytter has hung next to the film projections, reinforce the films’ symbolic moments. In addition, the places within the exhibition space where the films are shown also stand out: they are not only presented in the central gallery space, but also in a small side room, a kind of depot and in the emergency stairwell. In both these cases the spaces are rather dark and cramped – and, in keeping with the cliché, thus typical places to commit crimes. Through their obvious references to ‘film noir’, effective cuts and repeats as well as an openness, akin to that of the ‘Theatre of the Absurd’, Keren Cytter’s films reach far beyond the question of the reported crimes. They can be much more seen as poetic games which trace the limits of human existence, each of them ‘Endgames’ in a Beckettian sense, albeit firmly anchored in our media society.

The new work by Omer Fast consists of three parts. The project is based on a conversation with a West African refugee who had applied for asylum in London. In ‘Nostalgia I’ a British gamekeeper can be seen constructing a trap. The sound of this film however is an excerpt of the original conversation, in which the refugee as well gives a detailed explanation of how such an animal trap can be made. There then follows a dramatization of the conversation, in which two actors play the refugee and the artist. This conversation is not in any way a linear transfer of the refugee’s experiences, rather it follows the ideal course of the conversation as manipulated by Fast. It becomes clear how the person leading the conversation has clearly shifted from the artist to the refugee. The latter thus adapts his truth to meet the interviewer’s expectations. The bulk of the work is then formed by the film described by Omer Fast below which was elaborately shot in London. It takes up on particular details from the refugee’s life story and sets them in various scenes which either depict a possible future or perhaps rather an alternative past.

‘Judgment Day struck in 1980 and the world has been mired in a second Dark Ages since. Northern Europe is a wasteland and Britain has become a barren backwater where nomadic tribes roam across the dunes and raid one another for depleted resources. The only steady export from this once fabled island are migrants, who desperately stream across the European mainland in hope of a more peaceful and prosperous future in Africa. The story takes place inside and underneath a west-African colony, a collective gated community residing fortress-like above an old mine. A Refugee from Surrey is being interrogated as to the whereabouts of yet another tunnel used by the traffickers to smuggle Britons into the colony. He is offered the deal of his life and must choose between betraying his friends and securing his future. In the twenty-four hours he has to decide, his story wanders through the colony and is appropriated and recounted by its citizens to serve their own ends.’ (Omer Fast)

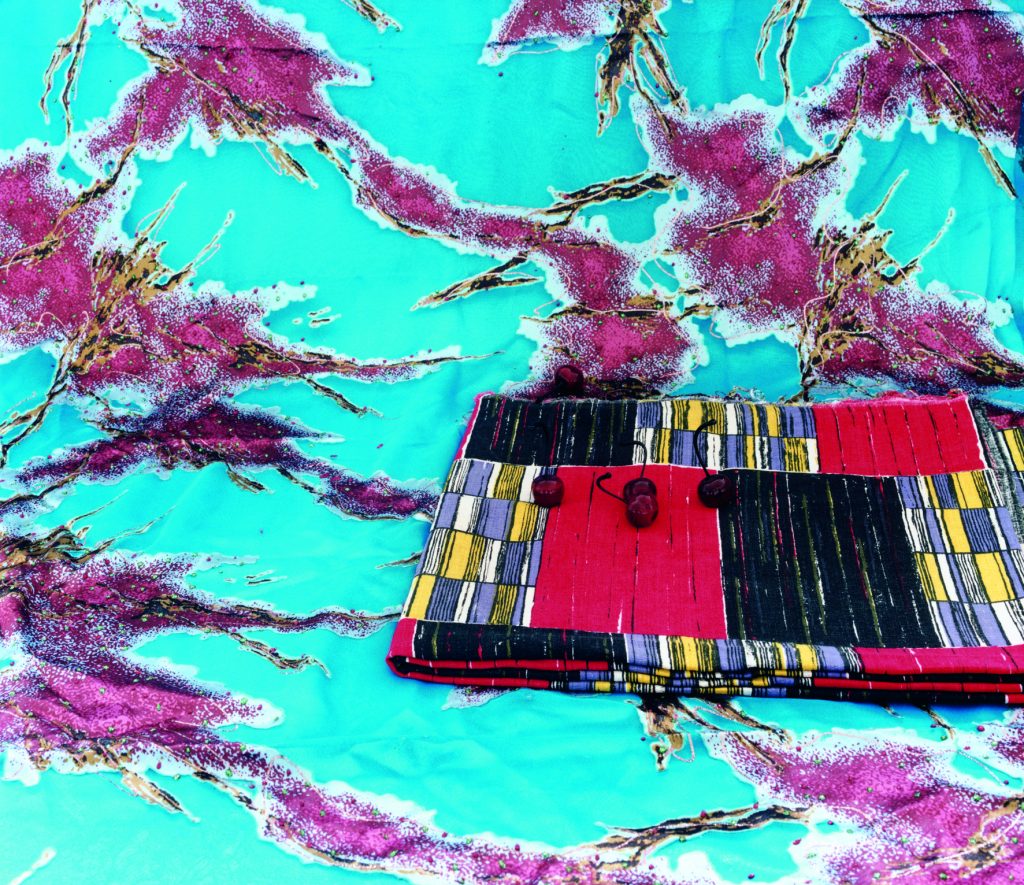

A field of sunflowers, five cherries on a piece of patterned material, a woman in front of a chequered cloth – the motifs in Annette Kelm’s pictures present us with puzzles. They appear simple and are not. Something strange, absurd has always found its way into the pictures. In the case of ‘Venice Zurich Brussels’, it is the garish colours and the fabric’s pattern. They are vaguely reminiscent of the fashion of the 70s. At the same time one can almost make out a map dotted with islands in the light blue and red pattern of the fabric. In ‘Michaela, Coffee Break’ the young woman’s awkward posture is arresting. Why is she holding the coffee cup so high? Are we being presented with an allusion to an old-fashioned gesture, such as were once found in portraits long ago? Through perplexities such as this Annette Kelm manages to arouse our curiosity to search for possible links. Some things have a coincidental, improvised air about them. Yet in all pictures there prevails what one could almost call an unsettling calm. Irrespective of whether they are of objects or people, there is no story behind the idiosyncratic photographs to divert us – they merely take stock of what we see. Essentially, Annette Kelm’s photographs are not so much snapshots but carefully staged depictions. The cherries for instance appear so artificial because that is exactly what they are: miniature works of art made from Murano glass in which the light and the artist herself are reflected. The images in ‘Michaela, Coffee Break’ on the other hand originally derive from black-and-white and colour Polaroids which have in turn been photographed with colour film. This obsolete technique explains the pictures’ depth of colour and revives certain traditions in the act of portraiture which, in combination with the patterned fabric in the background, makes it somehow reminiscent of motion studies from the early days of photography. The only difference being, in Annette Kelm’s works, nothing is moving. The way the photographs are presented in series only serves to document the slow task of portraiture itself – and thus the work of the photographer. The same holds true for ‘Archaeology and Photography’, a kind of surreal general assembly of books and courgettes. The book titles are suggestive of things, such as Annette Kelm’s passion for the discarded and amassed objects of the everyday which she recovers for use in her photographs. Her interest in bizarre material is evidence of this, as is her enthusiasm for Herbert Tobias, an important portrait photographer from the 60s and 70s whose works were later also used for record covers. Annette Kelm came across these record covers in an exhibition and photographed them on display in the museum. In the resulting series, ‘Herbert Tobias Record Covers, Berlinische Galerie ‘Blicke und Begehren’ 16.5.–1.9. 2008’, our view is not so much drawn to the photographic works themselves, rather to the cultural stratification which we yield to in any form of retrospective. It is precisely this interplay of curious referencing and memory that makes Annette Kelm’s works stand out, making her a unique figure in the younger generation of photographers today.

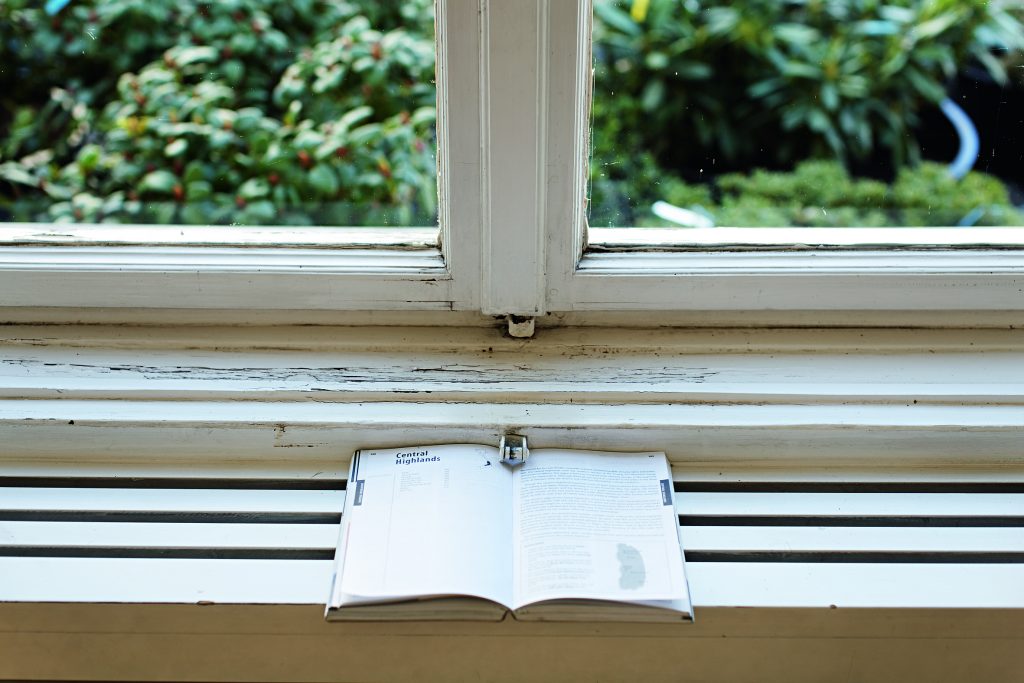

Danh Vo works with objects which have a history to them. His objects are not, however, defunct ready-mades as in Duchamp, but are rather deployed by the artist as a means of communication which prompt us to think of particular historical, political or even social implications. Danh Vo’s own origins in Vietnam, his family’s flight to Europe, his growing up in Denmark – all these factors play into the selection and presentation of the objects. Dahn Vo’s entry to the competition is primarily divided into three areas: a roof garden with rhododendrons which one sees right at the beginning of the exhibition, then the display of the chandelier and finally various other objects from Vietnam. The plants can be seen as a reference to Catholic missionaries who lived in Vietnam in the 19th century. While the chandelier, on the other hand, is nothing less than a sensation: Danh Vo has managed to acquire it from the legendary Hotel Majestic in Paris, an institution which played an important role in the political history of the twentieth century. The Vietnam Peace Accord was signed beneath these very chandeliers in 1973 for instance, something which Vo discovered in press photographs from the time. Vo steers our attention to the history of the country of his birth by combining the chandeliers with older works from 2007, all of which are historical Vietnamese objects from the 19th century. Completely different aspects of the country, hardly known today in Europe, are brought into view alongside the end of the Vietnam War: namely the imperial and violent expansionist policy of the Vietnamese themselves against the indigenous inhabitants of the mountainous regions of Vietnam. Since those belonging to this ‘montagnards’ fought in the Indochina and Vietnam War on the side of France and the USA respectively, they were repressed after the reunification of Vietnam. Colonialization by the French was actually perceived by these people as a form of liberation, associated with all the influences the Catholic missionaries brought with them. The impact of this mission can still be traced in the current situation of Catholics in Vietnam. Here too there is a connection to the roof garden designed by Vo, which solely contains plants that first found their way to Europe thanks to French missionaries, many of whom were persecuted in the 19th century, facing bestial methods of execution by the then ruling Vietnamese. Many of them were finally canonized as martyrs to the faith. The question as to the victims and perpetrators is thus turned once more on its head, which makes this work all the more appealing. In the exhibition itself such references as these are illustrated in texts on the walls. However the visitor has to develop his own version of the past.

First Jury

Massimiliano Gioni

Jessica Morgan

Beatrix Ruf

Janneke de Vries

Bernhart Schwenk

Second Jury

Daniel Birnbaum

Sam Keller

Christine Macel

Gabriele Knapstein

Udo Kittelmann