Preis der Nationalgalerie 2017

© Foto: David von Becker

Award Winner

Agnieszka Polska

(born 1985 in Lublin, lives in Berlin)

Jury statement:

Throughout her work, Agnieszka Polska ingeniously interweaves some of the most pressing issues of our time. She deftly creates a poetic and affective relationship between the visual and acoustic language of our digitally infused daily lives by using contemporary imaginary and cultural references–including scientific theories, early animation, and the utopian inclination of the avant-garde. In her exploration of multiple temporalities within our universe she destabilizes the very notion of humanity and humanness. As the personification of the sun in her film states: “My gaze was moving at constant speed, and everything was becoming irreversible the moment I observed it.”

Award Winner Exhibition

27 September 2018 – 3 March 2019

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin

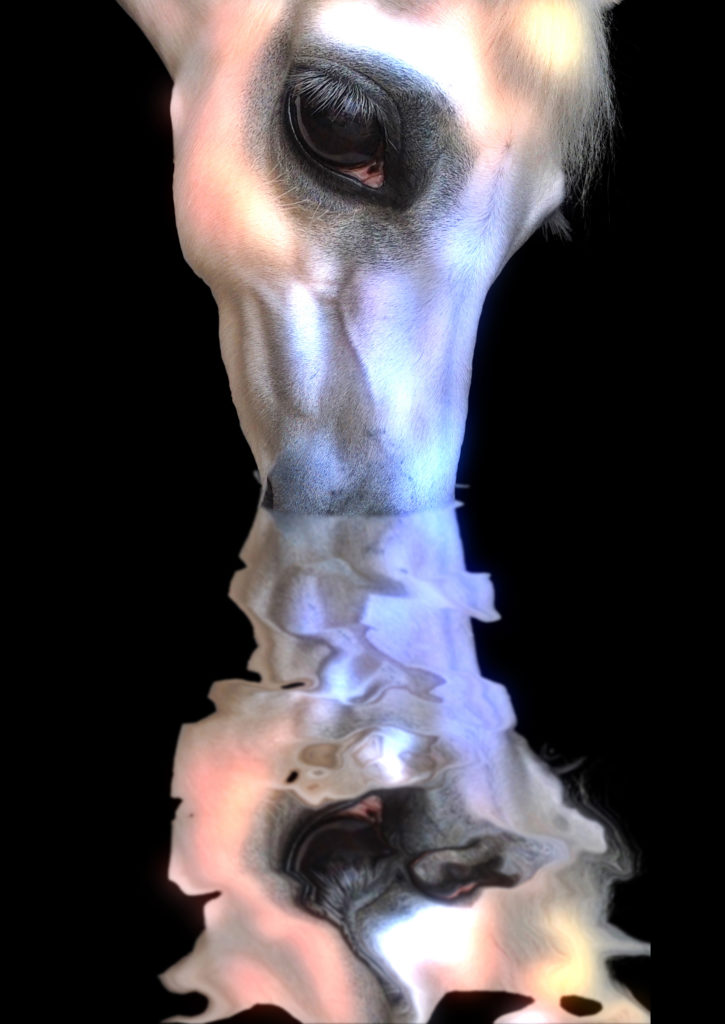

The Demon’s Brain

In The Demon’s Brain, a multichannel video installation created expressly for the exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, Agnieszka Polska grappled with the ethical question of how individuals can assume social responsibility amid the overwhelming demands of the present moment. The point of departure for the work was a collection of fifteenth-century letters addressed to Mikołaj Serafin, the custodian of Poland’s salt mines. In her videos, Polska melded live action with animation to tell the fictional story of a young messenger tasked with delivering these letters on horseback. Along the way, the boy loses his horse and he gets lost in the forest. There he has an unexpected encounter with a demon, whose monologue fuses Christian theological ideas with today’s developments concerning resource consumption, environmental destruction, data capital, and artificial intelligence.

The installation The Demon’s Brain, conceived for the museum’s Historical Hall, consisted of four large-format projection screens and a wall of texts. The films showed various scenes, which ran in an endless loop but were synchronized so that they commented on each other. A low-pitched, subliminal rhythm additionally united the scenes, helping to bridge gaps in time. After the demon has explained to the messenger how he himself can change the course of history, his recurring proclamation “It is not too late” reverberated through the hall, becoming an urgent appeal to the viewer.

In The Demon’s Brain Agnieszka Polska explored the possibilities for individuals to take personal action and assume responsibility for the problems facing the world. Although the messenger seems to heed the demon’s entreaty, we are forced to realize from today’s perspective that he was evidently unable to change things. Can individual action in fact have any influence on the complex processes in the world around us, and how do we decide which actions to take? Who can we trust to help us make this decision?

The wall of texts suggested a way out of this impasse. Excerpts from the historical letters to Serafin were interspersed with commentaries on the economic, ecological, and technological issues addressed in the work, taken from essays commissioned for the accompanying catalogue. The capacity of subjects to make a difference was thus juxtaposed with descriptions of abstract processes. What was revealed here is that active involvement, reflection, and exchanges with others, as well as the recognition of long-term patterns, can be the first steps to overcoming the ostensible powerlessness and ineffectiveness of the individual in the face of seemingly insurmountable crises.

Shortlist

Sol Calero

Iman Issa

Jumana Manna

Agnieszka Polska

Shortlist Exhibition

September 29, 2017 – January 14, 2018

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin

Jumana Manna makes films and sculptures that explore the ways in which social, political, and interpersonal forms of power interact with the human body. Her films weave together fact and fiction, autobiographical and archival materials, to investigate constructions of national and ideological narratives. The use of personal references is characteristic of her work, like in the exhibited film about musical traditions of the ethnic groups living around Jerusalem.

Similarly, Iman Issa addresses the relevance and the presence of inherited culture. At first, her sculptures from the “Heritage Studies” series appear Minimalist and oriented towards formal issues. However, they are a sculptural and personal appropriation of existing works of art and cultural assets seen through today’s view of the artist. Issa’s sculptures, that each have an additional text, thus resemble their archetypes in a different way than as visual and formal similarities.

We encounter an equally encrypted adaptation of cultural artefacts in the two animation films by Agnieszka Polska. Her references, however, originate neither from the distant past nor from high culture. Rather, her image collage is an encrypted inventory of the present that evokes the collective unconscious called the World Wide Web. Pervaded by an unsettling undertone, the connected films address the state of today’s world and our role and responsibility within it in a poetic and personal manner.

Like Polska, also Sol Calero works with an aesthetic that seems familiar. She is interested in a “Latin American identity” and its cultural codes. In her expansive installations, elements of vernacular architecture, the aesthetics of the tropics and social interaction are combined. Playfulness is connected to a critical approach that clarifies the paradox of “self-exoticization” and focuses on processes of exoticization that transform images and communities into stereotypes.

Award Winner Förderpreis für Filmkunst (Award for Cinematography)

Sandra Wollner and her film “Das unmögliche Bild” (“The Impossible Picture”)

Jury statement:

Sandra Wollner’s quiet meditation on the life cycle seems to hover between documentary and fiction. A film about life and death in many levels, it is also—and more fundamentally—a film about repetition: about the repetition of fate, the recurrent nature of memories and their similarity in this respect to the medium of film as a keeper of life in the form of a conserved and repeatable memory. Set in a large family home in 1950s Austria, the film uses the aesthetics and atmosphere of archival material. The attitude of the camera and the way the contents are told adopt the reality of a documented past experienced first hand by the female narrator, who at times also takes over the place behind the camera. She tells and shows us scenes from her life coming from the depths of her memory and looked at from a point beyond her lifetime. The viewer can hardly ward off the overwhelming feeling that she indeed allows us a glimpse into her own, self-experienced history and the story of her family.

Sandra Wollner convinced the jury with her mastery of the filmic language, which she employs with great accuracy, admirable creativity and ease. In both its carefully orchestrated and in its seemingly arbitrary moments, the film is always made with enormous precision. It is constructed as a cyclical puzzle where every part falls beautifully into place. Its pieces are interconnected in many ways, thus constructing a narrative structure that goes beyond linear narration. Blurring the boundaries between an experimental work of art, a documentary, and a cinematic film, Wollner’s work furthermore seems to mix the strengths of a novel, a painting, and a musical composition, using elements that are not inherently or necessarily filmic. The result is a work of art that is hard to describe in words.

First Jury

Meret Becker

Alexander Beyer

Natasha Ginwala

Alice Motard

Alya Sebti

Second Jury

Zdenka Badovinac

Sven Beckstette

Hou Hanru

Udo Kittelmann

Sheena Wagstaff